Blog Archives

BSI Weekend 2016: Historical Nostalgia, Anachronism, and Modernity

(Part 1 of my BSI Weekend 2016 write-up)

Last week, I attended, for the third time, what as referred to as the “Baker Street Irregulars Weekend,” though it’s really more like a week, lasting from Wednesday to Sunday. I’ve been meaning to write a post about my experiences attending one of these for several years now, but I think this year is about the right time to do it: my first two years, I was by far too starry-eyed to say anything coherent.

The reason I was so starry-eyed is because the Baker Street Irregulars is the primary Sherlock Holmes society in the world, started in the 1930s by author and publisher Christopher Morley. It has a long and illustrious tradition, and has influenced very much of Sherlockiana and the perception of Sherlock Holmes today. I would use the word “fandom” but it goes beyond that: the Baker Street Irregulars are a way of life, and almost an ideology. As a society, they are dedicated to the study of the Sherlock Holmes stories, referred to as “the Canon,” and membership is by-invitation only. Every year, they hold a dinner (similarly by invitation only) in New York City on January 6th, Sherlock Holmes’ birthday (which is not actually in the stories; in fact, there is nothing in the stories to suggest that it’s on January 6th. The reason we celebrate it on January 6th is because in The Sign of Four, Holmes and Watson are hungover on January 7th). However, though the dinner requires an invite, the rest of the week(end) is a full schedule of events that anyone can attend, and Sherlockians the world over convene in New York to celebrate the great detective – whom we call The Master.

This year has been a landmark BSI year for me, as I was invited to the BSI dinner for the first time (I’m not yet a member of the society itself, but one can hope). In keeping with the tradition of the event, which is meant to be secretive, mysterious, and even esoteric – and cannot be audio or video-taped – I will honor the intentions behind this grand event and won’t dwell too much on describing its details.

The view from the top of the Yale Club, where the dinner was held – a detail I think I’m allowed to share!

I can, however, say that the best description I’ve been able to come up with for the Baker Street Irregulars dinner is that it’s the annual get-together of a by-invitation-only literary society dedicated to the study of a fictional character, whom we pretend is real, and whose life and career was described in a series of texts we refer to as the Sacred Writings. Members are “invested” into the society on a mysterious basis using “investitures” that are phrases from the Canon – essentially, code names.

And when I put it like that, we do sound a bit insane. Which is quite all right, really.

In fact, I want to use this post to reflect on the culture of Sherlockiana – its beauty, and yet its irony. I have written, time and again, about the way that Sherlock Holmes is ultimately a highly modern figure, using the latest forms of technology, and representing secularism, reason, urbanization, industrialization – all those nineteenth century transformations. And yet the popular perception of him is so often nostalgic and anachronistic, of a Victorian figure in a deerstalker, back when there was fog and gas lamps and fireplaces and tea time in good old England. It’s a myth, and a romantic one, however inaccurate it is. However, it is not just the popular imagination that likes to associate Holmes with good old England – it is also Sherlockian culture that does it, however anachronistic it may seem. In fact, I would hazard a guess that much of this myth was constructed and propagated by the Baker Street Irregulars, many of whom were highly influential writers, actors, executives, lawyers, and politicians, among others, and who helped spread this myth.

In the early days of the BSI, Edgar W. Smith, the founder of the Baker Street Journal, referred to Sherlock Holmes as a “Galahad” from a time of Arthurian mythology and, in the first issue of the Journal, celebrated that very fog and gas lamps. G.K. Chesterton spoke of the stories as fairly tales, and Vincent Starrett, a Chicago man of letters, wrote the poem 221B, which is the best, most beautiful, and most poignant rendition of the myth and magic of Sherlock Holmes I’ve read, and these hallowed words are repeated at the end of every Sherlockian society meeting, including the BSI dinner:

Here dwell together still two men of note

Who never lived and so can never die:

How very near they seem, yet how remote

That age before the world went all awry.

But still the game’s afoot for those with ears

Attuned to catch the distant view-halloo:

England is England yet, for all our fears—

Only those things the heart believes are true.A yellow fog swirls past the window-pane

As night descends upon this fabled street:

A lonely hansom splashes through the rain,

The ghostly gas lamps fail at twenty feet.

Here, though the world explode, these two survive,

And it is always eighteen ninety-five.

It’s also, obviously, completely anachronistic- but, as the poem itself says, “only those things the heart believes are true. And there’s a reason that, despite the lack of these historical trappings in the Canon, this is what we cling to. As historian Michael Saler notes in the excellent book As IF, the BSI, as well as much of Sherockian scholarship, came into being around the time of the Great Depression and continued through into WWII and the Cold War. And in those trying times, Sherlock Holmes lived in a nostalgic and idealized version of 1895 to which these people could return.

And yet, though it’s the 21st century, that escapism is alive. The irony of this anachronistic “antiquarianism” had puzzled me for many years, as I was surprised that the careful scholars and devotees of the Canon, who knew how modern a figure Sherlock Holmes was, indulge in this nostalgically inaccurate romanticizing. But this year, attending the BSI dinner, and examining the practices of the BSI (many of which date back to the 1930s and really haven’t changed), I think I’ve come to understand why they have been preserved the way they have.

Every epoch has its escapism, of course – we have our own fair share of modern political events that we want to flee from into the comforting rooms of Baker Street. But I also think it has much to do not only with escapism, but with enchantment. As the aforementioned Michael Saler points out in his book, the late nineteenth century was perceived by many (including the sociologist Weber, who theorized it) to be a period of disenchantment due to the march of technology and progress. But Sherlock Holmes, as Saler points out, re-enchanted modernity, finding the romance in reason, the mystery in the quotidian, the magical in the commonplace. “There is nothing so unnatural as the commonplace,” he told Watson in A Case of Identity (this is, incidentally, probably the line upon which procedurals hinge, but that’s another topic for another day.

And that sense of (dis)enchantment is, I think, exactly what accounts for the practices of the BSI, which haven’t changed for the most part (which the exception of now allowing in women), and why I love them. I do, of course, rely on the conveniences of the twenty-first century, and wouldn’t ever wish to do without any of them – its transportation and communication technologies, its new forms of reference, and I similarly realize that there was nothing particularly magical or enchanting about the Middle Ages (the Plague and death in childbirth really don’t sound like fun). But there’s a certain joy in creating a magical, anachronistic version of a past reality. Just as readers did in the nineteenth century, we today want enchantment and magic in our convenient, technological, modern, positivistic lives. We want a sense of mystery and adventure, and yet reassurance, and the comforts of modernity. We as humans are picky, and difficult to please – for we want the conveniences of our cell phones, our trains and airplanes, or Wikipedia and Google, and yet while keeping these things, we want to preserve a sense of the magical and the mysterious in our modern world.

And that’s both influenced and kept alive the traditions of the BSI, I think. The Sherlock Holmes stories had mystery, intrigue, and enchantment in a modern world, and so does the BSI. A literary society with unwritten rules, with secretive meetings, with members given, essentially, code names (called “investitures,” they’re phrases taken out of the Canon), with a worldwide membership (but membership that must be earned, through a series of unnamed trials, which are not written down and never described) – well, that sounds like something out of a mystery novel. It’s like a combination of the eclectic membership of The Red-Headed League, the puzzles of The Dancing Men, the esoteric rituals of The Musgrave Ritual, the secret code of The Five Orange Pips, the ancient history of the Baskerville legend – all in one. We meet every year for the BSI dinner at the Yale Club, at which membership is exclusive, and you need an invitation to get in, and if you don’t think it looks like the Diogenes Club from the Canon, I don’t know what to tell you:

Its membership is limited to alums of Yale, and this system of university private clubs seems to have been inspired by British gentlemen’s clubs, of the kind to which Mycroft Holmes belonged. And, of course, Sherlock Holmes, being of respectable birth and having attended “college,” probably went to a respectable British university of exactly the kind that would have a club like this. Studying the Canon is called the Game, and it was inspired by Biblical scholarship at Oxford in 1911 – which gives it a long and illustrious history. At every dinner and gathering, poetic toasts are given to characters, places, and events from the Canon – yours truly has had the honor of giving one at a Sherlockian luncheon.

It’s a huge contrast to what one would call the “fandom” surrounding the newer adaptations like Sherlock and Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes –not because it’s somehow “less,” or less scholarly, or more frivolous, but because it’s based on an entirely different set of traditions. In the case of Sherlock, especially, the intriguing thing is that the show brings Sherlock Holmes back into modernity. It makes him, once again, a contemporary figure, as he would’ve been for his original readers, and not a historical one. I’ve always thought that Sherlock is actually the most accurate adaptation of Sherlock Holmes precisely because, instead of historicizing, it modernizes, which makes Sherlock fandom today rather analogous to Sherlock Holmes’ original readers. As Anne Jameson notes in an excellent book about fanfiction, Fic, fandom tends to be the first to pick up new forms of technology, because they are the ones striving to communicate with other fans and produce transformative work about the texts they like. This, of course, parallels the modernity of both Sherlock Holmes, who appeared in the most modern form of communication technology available to him (newspapers) as well as Sherlock fandom – which emulates his use of those contemporary forms of technology just like Victorian readers would have used the postal service (which had seven mail deliveries a day) to communicate with Doyle. In fact, there’s a lot of accuracy to both the modern technologies surrounding Sherlock and the fandom that uses them. At the same time, there’s a lot of history, and therefore cultural weight and significance around the BSI and their traditional way of studying and celebrating Sherlock Holmes.

Speaking to a friend of mine who regularly attends Sherlockian events, she told me that the BSI traditions are “preserved in amber” – left over from a previous time and preserved by devotees. By who knows how long those traditions will last? There’s been an influx of younger Sherlockians into the older traditions thanks to, ironically, the newer adaptations – and yet many of these younger Sherlockians are also part of Internet fandom. So as we get further into the new century, I wonder, will these traditions –which are almost a century old now – remain alive? Or will more modern forms of fandom replace these older traditions? Will they merge into some sort of weird Frankenstein-monster?

These are questions I’ve been left pondering. I have always been very pro-fandom, pro-Internet, pro-slash fiction, but at the same time, this weekend, and this dinner, has made me realize the value of keeping certain traditions alive, of preserving them, even in amber, even with their anachronism. That’s why I don’t mind how bizarre and, frankly, insane, we seem from the outside. There’s not only a method to the madness, there’s a meaning to the madness. As Vincent Starrett so eloquently said about Holmes and Watson, but which could very well be applied to Sherlockians:

“So they still live for all that love them well: in a romantic chamber of the heart: in a nostalgic country of the mind: where it is always 1895.”

Happy Destiel Day!

Each ship chooses a particular day that is in some way special and memorable in the history of that ship, and that fandom – having to do with how it came into being and what it means. In the case of Star Trek, for example, I recently witnessed “Space Husbands” day a couple of days ago, on the anniversary of the airing of “Amok Time” – the Star Trek episode in which Spock essentially has to have sex and die and then rolls around in the sand with Kirk (no, I’m not kidding). With that kind of homoeroticism (thanks, Theodore Sturgeon!), who can avoid shipping the two?

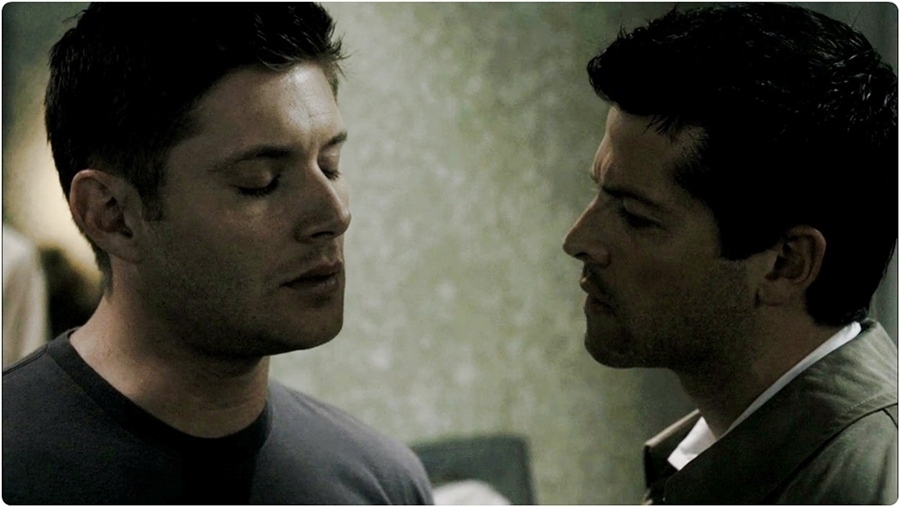

Well, September 18th is considered by the Supernatural fandom – or at least that contingent of it that loves Dean/Cas – to be Destiel day. It was on September 18th, 2008, that Castiel first walked onto the show and told Dean “I’m the one that gripped you tight and raised you from perdition.” Now, this obviously sounds pretty…suggestive, and their relationship didn’t get any less suggestive after that. Instead, it blossomed and flourished. Dean taught Castiel what it meant to be human, what it’s like to have choice and free will, why people and families and life matters more than paradise. And Castiel taught Dean how to change his worldview, how to trust, how to have faith, and how to believe in himself. The two of them went on a journey from being faithless to having faith, thanks to each other – but not faith in God or some other supreme being that washes his hands of the Apocalypse. They learned to have faith in each other, and together they formed what we call a “profound bond.” They changed each other’s worldview in so many ways, and what else could I ask for in a ship?

Their scenes together are really ridiculously suggestive, too.

I could wax poetic about these two for paragraphs, post many a screencap, analyze the romantic tropes in their relationship, talk about the representation of queer characters, explore how the relationship of these two ties into the themes of the show. Unfortunately, that would take way too long, so my small paragraph of waxing poetic will just have to do as a celebration of the profound bond between an angel and a human. So instead, I’ll leave you with a quote from the first page that comes up when you good “The greatest love story ever told”:

The story of a man afraid of flying, and an angel afraid of falling, who somehow met in the middle. The man who denied the existence of angels came to love one. The angel who never felt began to feel. The man who was saved from an eternity in Hell by an angel. The angel who fell in every way imaginable for a man. The man, with a clear path to escape, decided instead to stay in Purgatory for a year, searching for his angel, praying to him every night. Begging. When he found him, he held him; he told him that he needed him, that he’d get him out, even if it killed them both. The angel rejected his faith, his family, his home, and everything he knew, so he could keep the man safe. They stay together despite fate, despite what they are, because they refuse to be pulled apart.

Yes, that’s the top definition of Greatest Love Story Ever Told on Urban Dictionary. It’s the first thing that comes up when you Google it. I rest my case.

Motor City Comic Con: The Belated Thoughts of an Aca-Fan

A few months ago (and by a few I mean almost a year, because it’s only now that I have time to finish up this piece), I had the good fortune of attending my local comic con: Motor City Comic Con. Even though it’s been some time, I felt the need to write up my thoughts and experiences, especially because this convention (and most comic cons in general, I’d guess) has been a completely different convention experience from any other I’ve had, and I wanted to explore what those differences might be – in terms of fan interactions, in terms of what it is that we look for at conventions, and in terms of what brings groups of people together at conventions like this. That is, this is a bit of a sociological post, with observations and thoughts on conventions as a form of social interaction.

The past conventions I’ve gone two have fallen into two types: they’ve either been centered around a particular franchise (Supernatural, Stargate, Star Trek), or more academic conventions (such as the World Science Fiction and Fantasy convention) full of panels and discussions rather than autographs and entertainers.

Conventions centered around a specific franchise (usually run by Creation Entertainment), are a very special experience: you crowd hundreds (sometimes thousands) of people all obsessed with the same thing into one hotel for three days, and every single star is from that franchise and has worked on it some way. Sure, many of them have been on other franchises and of course there’s overlap, but mostly everybody’s there for one particular fictional universe (as an example, I’ll use Stargate, since most of my experiences have been with that franchise).

The thing with conventions like this is that, crowded into a hall with hundreds of people who love the same stories and characters as you do, there’s an indescribable sense of connection and kinship. There’s jokes and quotes and trivia constantly exchanged. There’s a trivia contest for that particular show/set of shows. There’s arguments over which scientist is the most attractive one (Rodney McKay). There’s a costume contest focused on that series. And when you’re all crowded into a hall together, the venue starts playing the theme song from that show, an actor/actress comes out, and you all cheer together – it’s an amazing experience. There’s this sense of wild enthusiasm of being a part of something big, of just loving this show so damn much and being with a bunch of people who share that enthusiastic, almost spiritual love for this amazing show that damn well deserves this adoration. Honestly, my first convention was a bit of a spiritual experience. I had, in internet-speak, “feels” about loving Stargate so much and about so many people loving Stargate.

The other type of convention, the conference sort of convention, I go to a lot less; I’ve been to a small handful,, and presented at one. This really is like academic conference: there were literally hundreds of panels on different semi-academic topics, from the portrayal of aliens in sci-fi to violence and fantasy and the portrayal of gender. A lot of authors were on these panels, but so were academics, bloggers, and fans. Sure, there were autograph sessions with a few particularly well-known authors (such as George R.R. Martin), but the majority of the convention (at least in my experience), happened in these panels. Here, there wasn’t quite the same sense of “we all love the same thing so much.” Sure, a lot of us shared love for things like Star Wars and Firefly and could reference it, but rather than a sort of spiritual enthusiasm, it was a much more academic enthusiasm that was in these panels. It seemed to me to be a lot more about getting to the bottom of some very important questions, albeit in a fun way, than about love and adoration and enthusiasm.

And then there’s Comic Con type conventions, which, as I discovered, work totally differently from the other kinds of conventions I’ve been to.

This is what a comic con type convention looks like, in general:

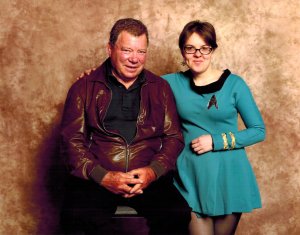

It’s a great big hall, mostly full of vendors selling everything from comic books to action figures to autographed portraits. Inside this great big hall, there’s also booths for all of the celebrity, comic, and wrestling guests, who spend most of their time (when they’re not doing panels and photo ops) signing autographs at these booths. There’s also one photo op booth, with different stars doing photo ops at different times, and, outside the main hall, several smaller rooms where the biggest stars (in this case, William Shatner, John Barrowman, etc…) held hour-long panels (for these you have to line up way ahead of time and let me tell you, that is stressful). There’s also a handful of other attractions in this big hall, including costume displays, replicas (such as R2D2), cars (the Ghostbusters car, for example), and a number of organizations such as the 501st Legion who have tables/displays/demonstrations. It’s like a big huge geek museum with lots of stuff for sale and lots of celebrities.

As cool as this is, though, what it means is that this isn’t a convention focused on a particular franchise. There are stars from everything, from television to film, and writers and artists. Are you a fan of Wonder Woman and the Swamp Thing? There’ll be something for you there. Star Wars? Check. Any TV show from soap operas to Star Trek? Check. As someone who’s previously mostly attended conventions dedicated to a specific franchise – conventions where everyone there was united by their love for one specific thing – I found this plethora of different stars and interests incredibly disorienting. We were all here because we’re all geeks who lead a certain lifestyle, collect autographs, want to meet the people behind our favorite franchises, and make room in our life for our geekiness – but every single person there wasn’t connected by their huge and immense love for just one thing. There was no wave of love washing over the entire hall for just one thing. There was definitely something for everyone, but you had to dig through a little for it: going through many of the vendors, you had to search for the posters and figurines you wanted. When I was standing in line, interacting with, and talking to people, there was always that initial period of trying to figure out what they were fans of, looking for that connection. I usually found it – after all, if you’re in the same photo op line, chances are you have something in common, some fandom, some place to start talking and connecting. But there was no automatic connection or point of reference to the things you loved the most. Going from star to star to get autographs and photo ops, you constantly had to switch from franchise to franchise – one minute you’re flirting with John Barrowman and having Torchwood feelings, and the next you’re telling William Shatner how damn much you love Captain Kirk. The second you work up enthusiasm for one particular actor or character, you’re already getting ready to stand in line for something else, for a completely different franchise, which evokes in you a completely different set of feelings. Perhaps that’s a personal quirk of mine, but I found it utterly strange to switch from passion to passion like this.

And then, of course, the question remains: how do you connect? Conventions are, after all, a form of interaction, a way to meet fellow geeks, a way to be at home with people who understand you, but when it’s a hall crowded with thousands of people who might all love different things, how do you make connections? What’s the appeal of a convention like this when everybody’s so different, sometimes united by nothing more than their identity of being a geek? And certainly “geek” is an identity in itself – one I proudly wear, despite whatever the Big Bang Theory has to say; certainly the people at this convention were “my people,” the ones who got what it’s like to be obsessed with something, but it’s not quite the same as being at a Stargate convention.

One of the answers to that question, I suppose, is cosplay. I never really got cosplay before. I knew what it was, of course, and I’d half-heartedly donned a uniform of some sort in the past, but most of the Stargate and Star Trek conventions I’d gone to didn’t have too many cosplayers, and it’s not too hard to cosplay Supernatural unless you don’t own any plaid. But here, there were incredibly elaborate (and I mean really elaborate), detailed, and sometimes very huge and heavy costumes. I saw dozens of stormtroopers and Jedi, a Darth Vader, several incarnations of the Doctor, a handful of Daenerys Targaryens, a few Castiels (Supernatural), a handful of Starfleet officers, and dozens of other superheroes, robots, and steampunk costumes that I did not recognize. These people wander around, crowding the hall, checking out the vendors, getting autographs and photo ops, and it’s pretty amazing to be crowded by fictional characters like that.

But most amazing is the way that cosplay serves as a form of connection. My first day, I donned a Starfleet uniform (a science officer from the original series, carrying the rank of commander, which I suppose would make me a first officer as well). I had the costume made on Etsy, and invested a good portion of money in it. Coupled with some knee-high boots, if I do say so myself, I looked pretty believable – and I had several people come up to me and request to take photos with me, and a handful more compliment me on my outfit (including William Shatner!) My second day, I threw on some denim and plaid to cosplay Dean Winchester, and ran into a Gabriel and a few Castiels from Supernatural, whom I took photos with as well. This all seems unremarkable except when you realize that in a hall crowded with thousands of people obsessed with hundreds of different fictional worlds, cosplay becomes that sort of connection. It becomes a way of proclaiming “this is what I’m a fan of!” and finding like-minded people in a huge hall. Most of all, however, cosplay becomes a sort of identity, that lets you identify people who have similar identities and connect through that.

Speaking of identity – there’s a lot of academic though about how identity is all just performance (Goffman and Judith Butler both write about this quite a bit), and a number of academics in the field of fandom studies have started applying this kind of theorizing about identity to cosplay as well. It seems to make sense: after all, when you don a costume, you, to some extent, don a personality; you make some sort of claim about who you are and what character means enough to you to dress up as them. You express your identity through fiction by making that fiction into reality. Whether you want to call it mimesis or performance, you take a piece of something that’s inspired your imagination and you create a physical product that allows others to see who you are and to relate to that identity. And again, in a hall crowded with thousands of people, this ability to wear your identity on your sleeve – and to use that identity to connect with others by using a common, fictional reference point, is pretty handy and pretty fascinating.

Plus, have I mentioned how cool it is to wander a convention hall and run into fictional characters? A number of the costumes were so elaborate that it felt like Darth Vader was actually strolling through the hall or that a Stormtrooper was following you. Especially if their faces were hidden, it really felt like fiction came to life, in, say, the form of a group of Jedi on secret Jedi business. It was like a number of fictional worlds had all come to life at the same time, and all the fictional characters were dumped into one place to walk around. I can’t explain just how amazing and breathtaking it is to see all these fictional characters become real and just sort of…wander around, just like you do, buying stuff and talking to people. Part of the charm, I think, is not just cosplaying yourself, but in creating that atmosphere where the fictional worlds come to life for the people around you, who feel like the things they’re invested in exist, that they’re somehow real because look, there’s Jedi and stormtroopers walking around, so it clearly must be Tatooine.

Which leads me to my next point about what brings people to conventions. Why do people come if they don’t come for that kind of uniting love of one franchise? Of course, they come to take photos with stars and get autographs and buy stuff and ask questions. But I think all of this – as well as all the cosplay and all the fictional worlds coming to life – all hint at a deeper need. One that I think William Shatner hit upon pretty brilliantly in his panel: it’s a sort of ritual.

Shatner spoke of science fiction in itself as a sort of mythology. Normally, mythology attempts to explain how the world works – which is why there were gods of the sea and weather and fire and rain and whatnot, and Prometheus myths, and giants. Nowadays, we’ve explained the sun and the moon, but there are still mysteries in the universe – so much we don’t know. What’s out there? How much don’t we know about what we don’t know? Science fiction, to some extent, fulfills that mythological need – it attempts to explain what might be out there, gives us ideas and possibilities, and makes us think about them. It doesn’t always provide answers, but it does provide perspectives. Star Trek was particularly great at this, taking us to other planets and other cultures and helping us to understand what might be out there and how the universe might work. And conventions are – well, responses to that sort of mythology. They’re a way for us to find answers and enchantment in a more modern world, where science and reason play a role in that mythmaking but where there’s still wonder.

And indeed, there seems to be a form of ritual about these conventions, where people are brought together by this sort of modern mythology in ways that are, in some ways, ritualized.

In a book on audiences and performance, two authors (Abercrombie and Longhurst) point out the ritual, almost sacred nature that is involved in being a “simple” audience – that is, in attending the theatre, or a concert, where there are certain unspoken rules of etiquette, certain actions that are always followed, certain scripts according to which the audience behaves, which gives the entire endeavor a sort of ritualized, and therefore sacred, experience. They also point out the way that theatre was often tied to the sacred in the past – from the theatre of ancient Greece to the medieval church plays – and indeed, I agree with them that there is something ritualized and sacred about going to the theatre, about going to see a performance – or about going to see a panel and interacting with an actor or artist as one would in a theatre.

I think this form of the sacred, and of ritual, extends much further, though. Without going too academic on all of this, I think there’s an element of seeking out the sacred in collecting autographs or comics our figurines (artifacts, really), a certain element of ritual in the way that encounters with stars happen (photo op and autograph etiquette is usually the same at every convention, and there are certain very strict rules in how you can approach and interact with someone, who’s placed on a pedestal by virtue of being a celebrity). These celebrities, rather than being representatives of a religion, are to some extent representatives of a mythology – the mythology of science fiction, of comics, of geekdom, that William Shatner talked about – and our interactions with these people are highly controlled, highly ritualized because of it (you can do this, you can’t do that), which gives it all a character of the almost sacred (“William Shatner signed my Enterprise! John Barrowman touched my butt!” kind of sounds like “this saint laid his hands on me!”)

So I think, inadvertently, Mr. William Shatner hit upon something that it might behoove academics of fandom and of popular culture to study – the way that science fiction, popular culture, and geekdom, are a form of mythology and a form of the sacred in our modern day culture, and the way that conventions are not only a manifestation of “worship” (in a loose sense of the word) of the sacred, but also the way that people connect through their investment in this mythology (for, like it or not, religion has to a certain extent often been a way for people to connect, even as it’s been the source of religious wars and sects).

And that finishes up my post as an aca-fan, as a geek who’s also an academic, who enjoys reveling in the wonder of meeting Captain Kirk but who also likes to think about the processes involved in this interaction.